What We Must Remember

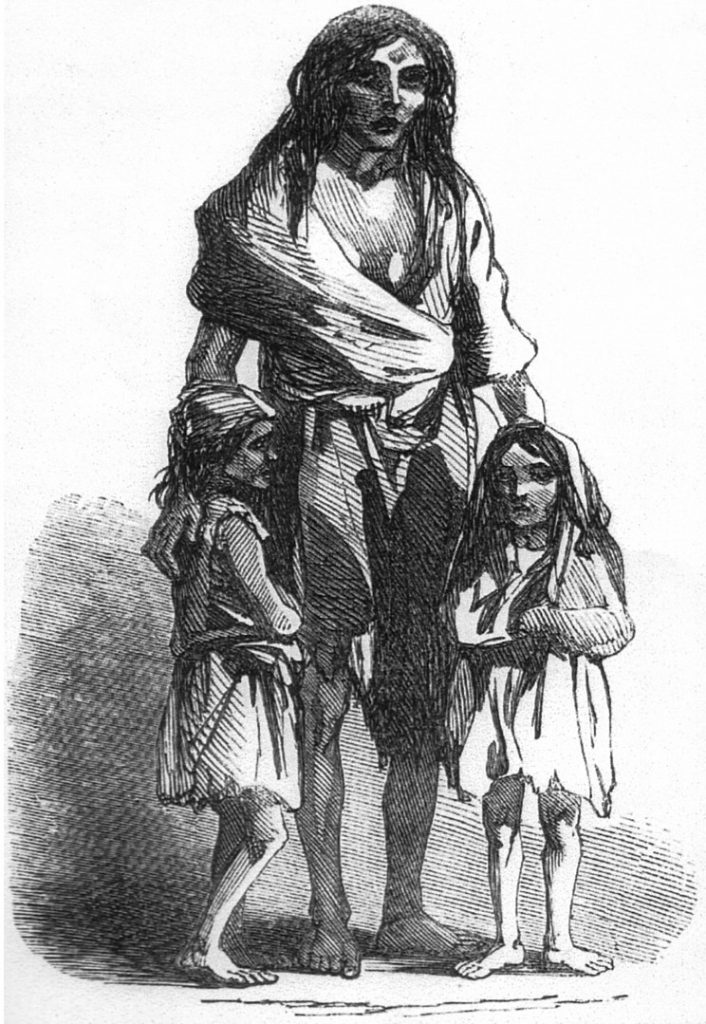

Her story is briefly this:– ‘. . .we were put out last November; we owed some rent. I was at this time lying in fever. . . they commenced knocking down the house, and had half of it knocked down when two neighbours, women, Nell Spellesley and Kate How, carried me out. . . I was carried into a cabin, and lay there for eight days, when I had the creature (the child) born dead. I lay for three weeks after that. The whole of my family got the fever, and one boy thirteen years old died with want and with hunger while we were lying sick.

by Illustrated London News, December 22, 1849

by Marty McCormack

On what is going to be looked upon as a historical St. Patrick’s Day, I think there is a great lesson to be learned from the past. Irish past, to be exact, and in this case, many possible parallels can be drawn between what happened starting in 1845 and what is going on in 2020.

In 1845, a blight of the potato crop, Phytophthora infestans, made its way from Mexico throughout North America. The blight was not something that killed people outright, but rather the tuber of the plant, causing leaves to wither and the potato to literally rot in the ground. Like the virus we are now facing, it did spread globally and eventually to Europe to the one country that would feel its worst impact: Ireland.

The potato called the “Irish Lumper” was a big potato, and because of it being easy to grow, abundant and nutritious, the Irish race grew in stature and number as well. Each man, woman and child ate potatoes. A grown man could easily devour ten pounds a day. Each small plot of land was made available to this godsend for the second class citizens of Ireland. I say “second class,” as they were a conquered and subjected peasant people.

Ireland was part of Britain, at that time the most powerful nation on Earth and ruled by a government that ignored the initial warnings that scientists gave. As one third to about half of the crop was wiped out, hunger set in. Despite these warnings, the government dithered. Upon hearing these warnings, the British Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Heytesbury, suggested people “not to be alarmed,” that these warnings were premature, that scientists were inquiring into all those matters. With time lost, the blight proliferated and the Irish people began to starve.

The British government did little to help the Irish. As the situation grew dire, a new prime minister, Lord Russell, and with his Lieutenant of Irish relief, Lord Trevelyan, took power. They were Whigs, a very conservative government party with a “government that governs best” philosophy, in today’s parlance called “laissez-faire economics.” Whigs also harbored a deep-seated dislike of the Irish, whom they considered at best a mongrel race. And Trevelyan, who was supposed to be helping the Irish said the famine was “the judgment of God on an indolent and unself-reliant people,” and as God had sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, “that calamity must not be too much mitigated.”

What resulted were years of calamity, with the darkest year 1847. Unlike our current crisis, with reports of some people hoarding, any other food source that was not the potato in Ireland was exported to Britain itself. Part of this was in part because the British government believed that the government was better served to have non-government agencies step in and handle the crises. That way the vast majority of taxpaying (non-Irish) subjects would not feel the pinch of taxation for relief efforts. So, business as usual. The landlords, who were Anglo-Irish that were part of the British aristocracy, continued to charge the Irish for “rent” on their lands. And they continued to export the very food the Irish themselves raised, but were not allowed to eat. This is why Irish refer to the Potato Famine by its proper name An Gorta Mor, or The Great Hunger.

The result was that a million people in Ireland died of starvation or starvation-related disease. Many left never to see Ireland or their families again. On our townland of Bolinree were the remains of eight homes. Whole villages were either wiped out or displaced. The resulting turmoil led to revolution throughout Europe. It could be argued that the foment did not truly play itself out until the end of World War Two.

So here we are today. Saint Patrick’s Day. And as horrible as it is to be faced with the uncertainty of Covid-19 and that there is currently no treatment for it, I can only imagine the horror of dying the slow, painful death of starvation. And also to witness your family dying, while just outside your door, if you were allowed to own a door. Casks of Irish butter, and Irish cattle being brought to port for the Empire. People were too starving to remove bodies of their loved ones, who lay in close proximity. Like the Italians of today, the system was overwhelmed in gross negligence and underwhelmed in a lack of conscience.

While the story of the Great Hunger is something that calls for at least a volume of books to address all the details of “what went wrong,” it is notable to see some glimmers of what went right.

Americans of the time rallied to help fight the famine. Abraham Lincoln, then a senator in Illinois, gave $10 (about $370) to help alleviate the suffering. The Choctaw nation, a decade and a half after their own suffering in the Trail of Tears, raised $170 (over $5000) to help the Irish. According to Wikipedia, Senator Henry Clay in 1847 said, “No imagination can conceive—no tongue express—no brush paint—the horrors of the scenes which are daily exhibited in Ireland.” Clay reminded Americans that charity was the greatest act of humanity. In total, 118 vessels sailed from the US to Ireland with relief goods valued to the amount of $545,145. That could be a lot of food in the 1840s. It was a shining moment of solidarity prior to the Civil War. And ultimately Ireland rewarded America with her people and planted a Celtic stake in this country that even today transcends the Irish themselves.

So, Saint Patrick’s Day, with its green beer, boisterous costumes, and high stepping dancers is totally out of place this year. In one way it is a blessing to have all of that hooplah stripped away to what has been the dark kernel of truth about the holiday. Underlying it is something that even we of Irish heritage loathe to recall. Better to have the party and the dyed green river.

But today, we need to recall it.

We as a people have survived much worse. We, like other peoples who have suffered intolerance, injustice, and natural and artificial calamity, did survive.

We embraced this new world, married others of different lands, embraced different faiths, championed different causes, fought wars to redress wrongs in the world and transformed the world into something much bigger than it could have ever been had the An Gorta Mor not taken place.

As we face an uncertain future, struggle to make sense of what is fact and what is fiction, and find ourselves downright frightened for us and our children, we need to remember that our forebears did the same, too. And with the same courage, the same benevolence for others, and faith, we will see through this great crisis. And we will make something even more beautiful because of it.